rate limiting and the token bucket algorithm

I recently fell down the rabbit hole of rate limiting and decided to build my own token bucket implementation in Go. This blog covers what rate limiters actually do, why do we need them, and how you can build one from scratch yourself (preferably with a cup of coffee in hand).

the project repo: github.com/jerkeyray/tokbuk

what is a rate limiter?

A rate limiter is a control mechanism that limits how frequently a client can do an action within a system. In HTTP terms, a rate limiter limits the amount of client requests to be sent within a specific period. If the API exceeds a certain number of requests defined by the rate limiter, all the excess calls are blocked.

why do we even need one?

Ideally a rate limiter seems like an optional feature, I mean why do we even build such highly performant distributed systems with auto-scalers and load balancers which can handle high traffic if we're gonna be rate limiting our servers? If your system is made to handle scale why bother setting up a rate limiter?

> autoscaling takes time

Cloud autoscaling is a mechanism on cloud platforms that automatically adjusts the number of running server instances based on the real-time load. It waits for metrics such as CPU usage, memory usage, request latency to cross certain thresholds and then spins up new instances. This can take up to a minute depending on the cloud platform. During this gap our service is exposed, this is where our rate limiter comes in and protects the system while autoscaling is still catching up.

> load balancers don't give a shit about your application context

A load balancer is a very simple creature. It knows how to:

- accept a connection

- reject a connection

- forward a connection to another server instance

It cannot differentiate between:

- a lightweight GET request that returns immediately.

- an expensive POST request that triggers database writes. It treats them all the same.

A load balancer operates blindly without the context of our application, a rate limiter on the other hand has this understanding. It can enforce limits based on client identity or request type.

> saves you from getting DDoSed and ensures fairness

Not all clients behave the same. Some follow predictable usage patterns while others treat your API like an all-you-can-eat buffet. A rate limiter protects you from this uneven and often hostile behaviour.

There are few layers to this:

>> preventing unintentional abuse

Most abuse isn't even malicious. It's just some dev out there with his vibe-coded app retrying aggressively because someone forgot exponential backoff or a misconfigured cronjob. A rate limiter acts as a seatbelt here. Even if one client misbehaves accidentally, it can't take the whole service down with it.

>> defending against application-layer DDoS traffic

Large-scale DDoS attacks get handled by CDNs and network filters, but smaller "application-layer" floods still slip through. Even something as simple as just one client hitting an expensive endpoint too fast can overwhelm our CPU or database. A rate limiter caps how much any single resource can spend, stopping abuse before it slows down everyone else.

>> ensures fair usage

If your service has shared resources, you want your clients to consume them fairly. Without a limiter, one heavy user can drown out everyone else and starve normal users.

This is why robust systems need distributed or shared-state rate limiters.

requirements of a rate limiter

Before writing any code, we need to be clear about what the requirements for a rate limiter are. A good rate limiter has very specific expectations on both correctness and performance.

>> functional requirements

For a given request a rate limiter should return a boolean value on whether the request is throttled or not. This is based on who the client is and how many requests they've recently made.

>> non-functional requirements

- low latency because if the limiter is slow, the whole API becomes slow.

- high accuracy and the limiter should enforce the limits precisely.

- should be scalable and handle high concurrency without breaking down.

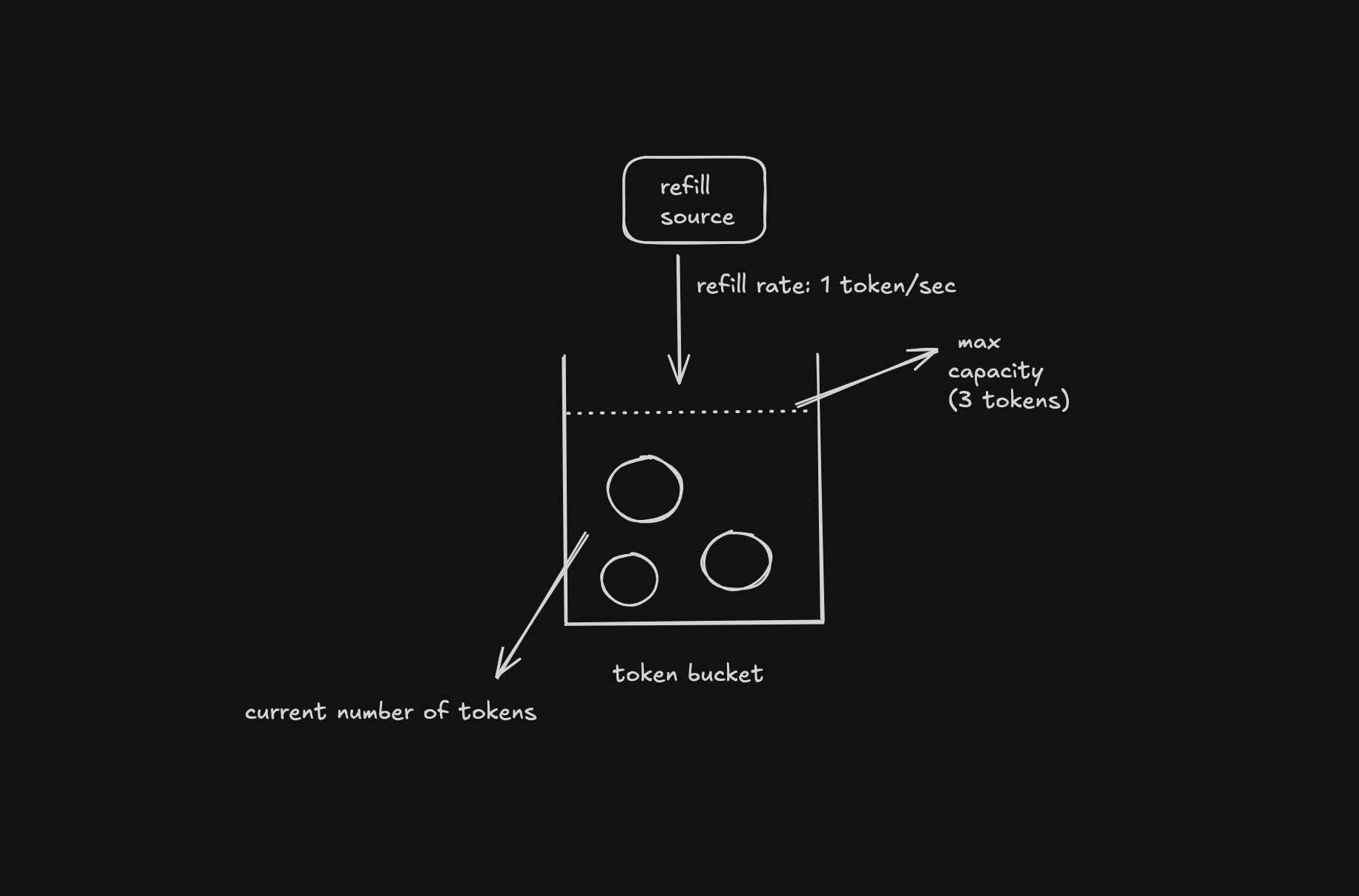

the token bucket algorithm

The idea behind the algorithm is very simple, you have a bucket that slowly fills with tokens and a rule that every action must "pay" for itself by consuming one.

It is designed for a fixed average rate of traffic while still allowing for short bursts of intense activity.

> the bucket

Imagine a container with fixed capacity. This capacity defines the maximum burst a client is allowed to make. If a bucket can hold 10 tokens then the client can perform 10 actions in rapid succession without violating any limits. The bucket never grows beyond its boundary, once full, it patiently waits for tokens to be used.

> the tokens

A token is just a metaphor for permission, one token equals to one allowed request.

> the refill rate

Tokens drip into the bucket at a fixed, continuous rate. Something like five tokens per second.

> controlled bursts

The best part about the token bucket is its graceful handling of bursts. When a client has been quiet for a while, unused tokens accumulate. When activity resumes, the client can make several quick requests in succession, spending the saved tokens. This behaviour reflects real usage patterns.

> when the bucket runs dry?

Eventually, when the requests arrive way too quickly, the bucket will run dry. It is now the rate limiter's job to say no to any more incoming requests.

The request is rejected often with a HTTP 429 (too many requests) status code and the client must wait for new requests to appear.

> why this algorithm is kinda nice

- guarantees a stable average rate

- allows short bursts as well without compromising system health

- is very simple to implement and computationally efficient

implementing a token bucket in go

Before we start implementing this thing, take a moment and open the repository: "https://github.com/jerkeyray/tokbuk".

I’m assuming you're comfortable with the basics of go and concurrency but even if you aren't, I'll try to keep things simple. And if something does feel unfamiliar, just go ask gippity the things you don't quite grasp.

Now let's start with the heart of the system: the token bucket.

tokbuk/internal/limiter/bucket.go

package limiter import ( "sync" "time" ) type TokenBucket struct { mu sync.Mutex // allow only one goroutine to read/modify this bucket at a time capacity int64 // burst allowance (max tokens bucket can hold) tokens float64 // current available tokens (float because refill can be fractional) rate float64 // tokens regenerated per second last time.Time // when last refill was calculated now func() time.Time // injected time source so tests can control time } // create bucket, fill it to max capacity, record time of creation and set refill rate func NewTokenBucket(capacity int64, ratePerSecond float64) *TokenBucket { if capacity <= 0 { panic("capacity must be greater than 0!") } if ratePerSecond <= 0 { panic("ratePerSecond must be greater than 0!") } now := time.Now() // used to calculate elapsed time for refill return &TokenBucket{ capacity: capacity, tokens: float64(capacity), rate: ratePerSecond, last: now, now: time.Now, } } // return true if request is permitted else false func (b *TokenBucket) Allow(n int64) bool { if n <= 0 { return false // reject zero or negative token requests } // lock the mutex b.mu.Lock() defer b.mu.Unlock() b.refill() // if enough tokens available spend them and return true if float64(n) <= b.tokens { b.tokens -= float64(n) return true } // deny request return false } // generate tokens based on time passed since last refill func (b *TokenBucket) refill() { now := b.now() // current time elapsed := now.Sub(b.last).Seconds() // current time - timestamp of last refill if elapsed <= 0 { return } add := elapsed * b.rate // tokens regenerated based on time passed if add > 0 { b.tokens += add // add them to the bucket // if bucket overflows set tokens to max capacity if b.tokens > float64(b.capacity) { b.tokens = float64(b.capacity) } b.last = now // update last refill timestamp } } // replace real time with a controllable clock for deterministic testing func (b *TokenBucket) WithClock(now func() time.Time) *TokenBucket { b.mu.Lock() defer b.mu.Unlock() b.now = now // swap out the time provider b.last = now() // resets last return b }

We already have a mental model for how a token bucket works. Rather than walking through the code line by line (already heavily commented and self-explanatory), let's look at the design choices that shape the implementation.

Think of the token bucket as a deterministic state machine. Every request shifts the bucket from one state to another and the rules which govern these states are simple and strict.

The bucket's state is defined by these five things: capacity, tokens, rate, last, and now. These fields form the machine's memory. Every call made to Allow() causes the state machine to evolve: it calculates how much time has passed, regenerates tokens, fills them up to the max capacity, and either accepts or rejects the incoming request.

Every update follows a fixed sequence:

- compute time elapsed since

last. - generate new tokens.

- cap tokens at

capacity. - accept or reject the request.

- update

last.

concurrency and the token bucket

Since the rate limiter lives directly in the request path, which means many goroutines may call Allow() at the same time. All of them want to read and update the same shared data which is the number of tokens, the last refill time and the refill rate. If we let goroutines modify these values at the same time, the bucket would break instantly. To avoid this, the implementation uses a single mutex.

Whenever a request calls an Allow() function, the first thing it sees is:

b.mu.Lock() defer b.mu.Unlock()

This guarantees that only one goroutine can update the bucket at any given time.

Now let's work on the Bucket Manager.

The TokenBucket we implemented earlier works perfectly for a single stream of requests. But real backend systems don't just have one "client", they deal with hundreds, thousands, sometimes millions of clients at the same time. This is why we need a layer that manages one bucket per client. Each client gets its own isolated rate limiter with its own refill schedule and its own burst allowance. This is the purpose of the Bucket Manager.

tokbuk/internal/limiter/manager.go

package limiter import ( "sync" ) // maintain a collection of token buckets // one per unique client (IP, userID, APIKey, etc) // ensure each client gets its own unique rate limiter instead of sharing a global one type BucketManager struct { mu sync.Mutex buckets map[string]*TokenBucket // map client key -> its token bucket } func NewBucketManager() *BucketManager { return &BucketManager{ buckets: make(map[string]*TokenBucket), } } func (m *BucketManager) GetBucket(key string, capacity int64, rate float64) *TokenBucket { m.mu.Lock() // prevent concurrent access to the same map defer m.mu.Unlock() // return existing bucket if key already exists if bucket, ok := m.buckets[key]; ok { return bucket } // if key doesn't exist, create and register a new bucket // newly created buckets start full and use the provided capacity/rate bucket := NewTokenBucket(capacity, rate) m.buckets[key] = bucket return bucket }

The BucketManager keeps a map of client identifiers. An identifier is just a string that could represent IPs, user IDs, API keys, or anything that uniquely identifies a client.

When a request comes in:

- The manager checks the map for a bucket matching that client.

- If it exists, return that bucket.

- If not, create a new TokenBucket and return it.

This ensures we only end up creating buckets for clients who actually send traffic.

Since multiple goroutines may try to access or create buckets at the same time, the map is protected by its own mutex. Once a bucket is retrieved the bucket's own mutex (the one we added earlier) takes over.

If you're wondering why we need layered mutexes here instead of just using one (cause i was thinking the same), the reason is simple: we need two mutexes because we are protecting two completely different shared resources. The manager's mutex guards the map of all buckets, which interacts with all the clients. Each Token Bucket on the other hand has its own mutex to protect its own token state, which only its client's request changes. If we only had one global mutex a request from client A would also block client B from using its own bucket. With two locks, the map stays safe and each client's bucket can update independently.

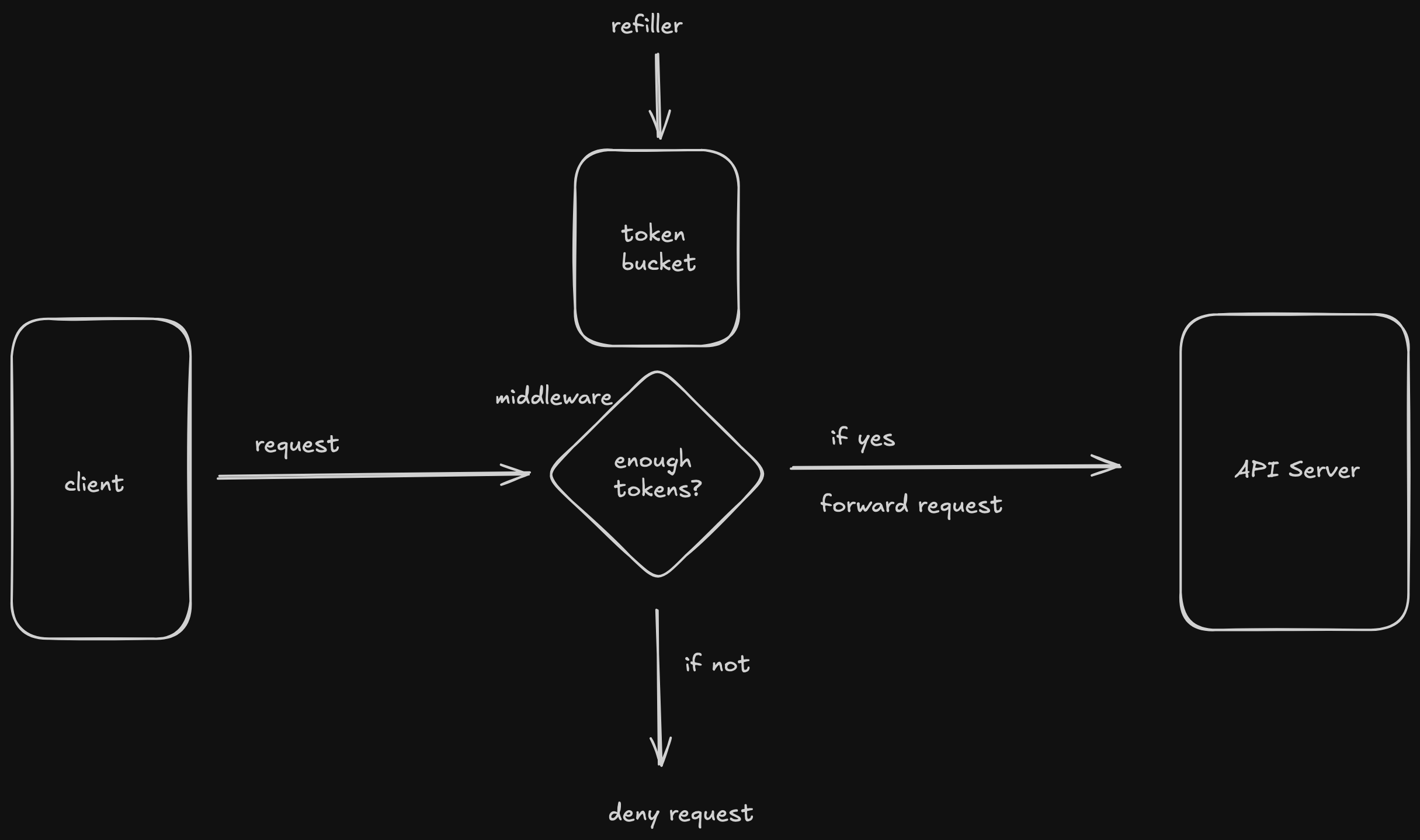

Now that we have a functioning rate limiter, we need a way to place this logic in an actual HTTP server so that every incoming request flows through this limiter before reaching any application logic. This is where middleware comes in.

tokbuk/pkg/middleware/ratelimit.go

package middleware import ( "github.com/jerkeyray/tokbuk/internal/limiter" "net/http" ) // extracts client's unique identity string from the HTTP request // the identity determines which token bucket will be used by the request type KeyFunc func(*http.Request) string // returns middleware that applies rate limiting to an http.Handler func RateLimit( manager *limiter.BucketManager, capacity int64, rate float64, keyFunc KeyFunc, ) func(http.Handler) http.Handler { // return middleware wrapper return func(next http.Handler) http.Handler { // return handler that enforces rate limiting return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { key := keyFunc(r) // extract identity of caller bucket := manager.GetBucket(key, capacity, rate) // get existing bucket or create a new one if new key // check if request is allowed if !bucket.Allow(1) { http.Error(w, "rate limit exceeded", http.StatusTooManyRequests) return } // if allowed proceed to actual request handler next.ServeHTTP(w, r) }) } }

what does this middleware do?

- Extract the client's identity using KeyFunc (could IP, API key, whatever).

- Use BucketManager to fetch that client's TokenBucket.

- Calls Allow() to check whether the request is allowed or not.

- Returns 429 if request is not allowed.

- Else forward request to the actual Handler.

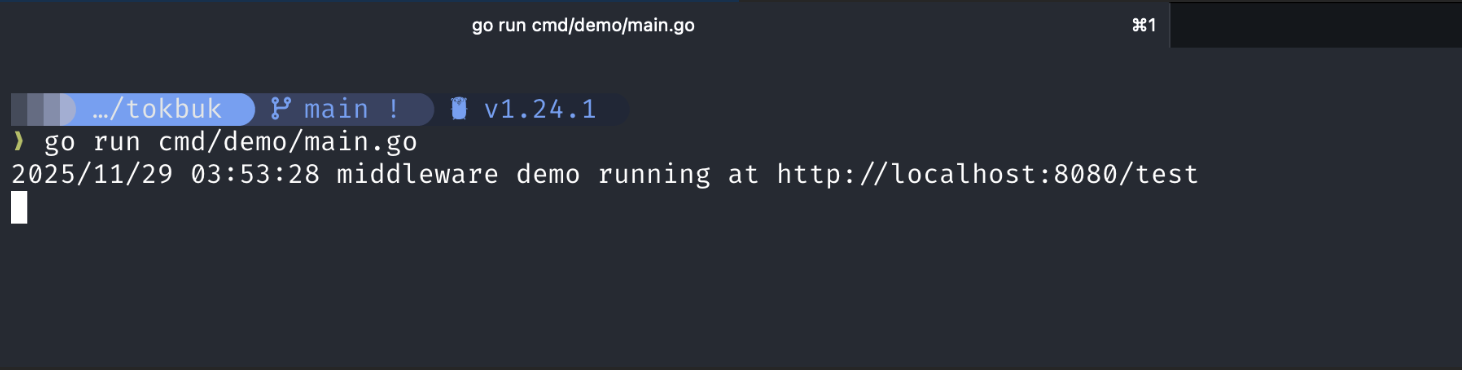

Now the only thing left is to plug everything into an actual HTTP server and test the limiter out.

tokbuk/cmd/demo/main.go

package main import ( "fmt" "log" "net" "net/http" "time" "github.com/jerkeyray/tokbuk/internal/limiter" "github.com/jerkeyray/tokbuk/pkg/middleware" ) // KeyFunc implementation that identifies clients by IP address. func clientKey(r *http.Request) string { ip, _, err := net.SplitHostPort(r.RemoteAddr) if err != nil { return r.RemoteAddr } return ip } func main() { manager := limiter.NewBucketManager() // build rate limit middleware with capacity = 3, rate = 1 rl := middleware.RateLimit(manager, 3, 1, clientKey) // create router mux := http.NewServeMux() // wrap "/test" handler with rate limit middleware mux.Handle("/test", rl(http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "allowed") }))) // configure and create HTTP server server := &http.Server{ Addr: ":8080", Handler: mux, ReadHeaderTimeout: 2 * time.Second, } log.Println("middleware demo running at http://localhost:8080/test") // start server and exit if it fails log.Fatal(server.ListenAndServe()) }

What we just did:

- Create the BucketManager.

- Wrap the

/testhandler with our RateLimit middleware. - Identify clients by their IP address (r.remoteAddr), so each IP gets its own Token Bucket.

- Any requests allowed by the bucket reaches the handler, else return an immediate HTTP 429 response.

- Start an HTTP server on port 8080 so you can hit the

/testendpoint and watch the limiter kick in.

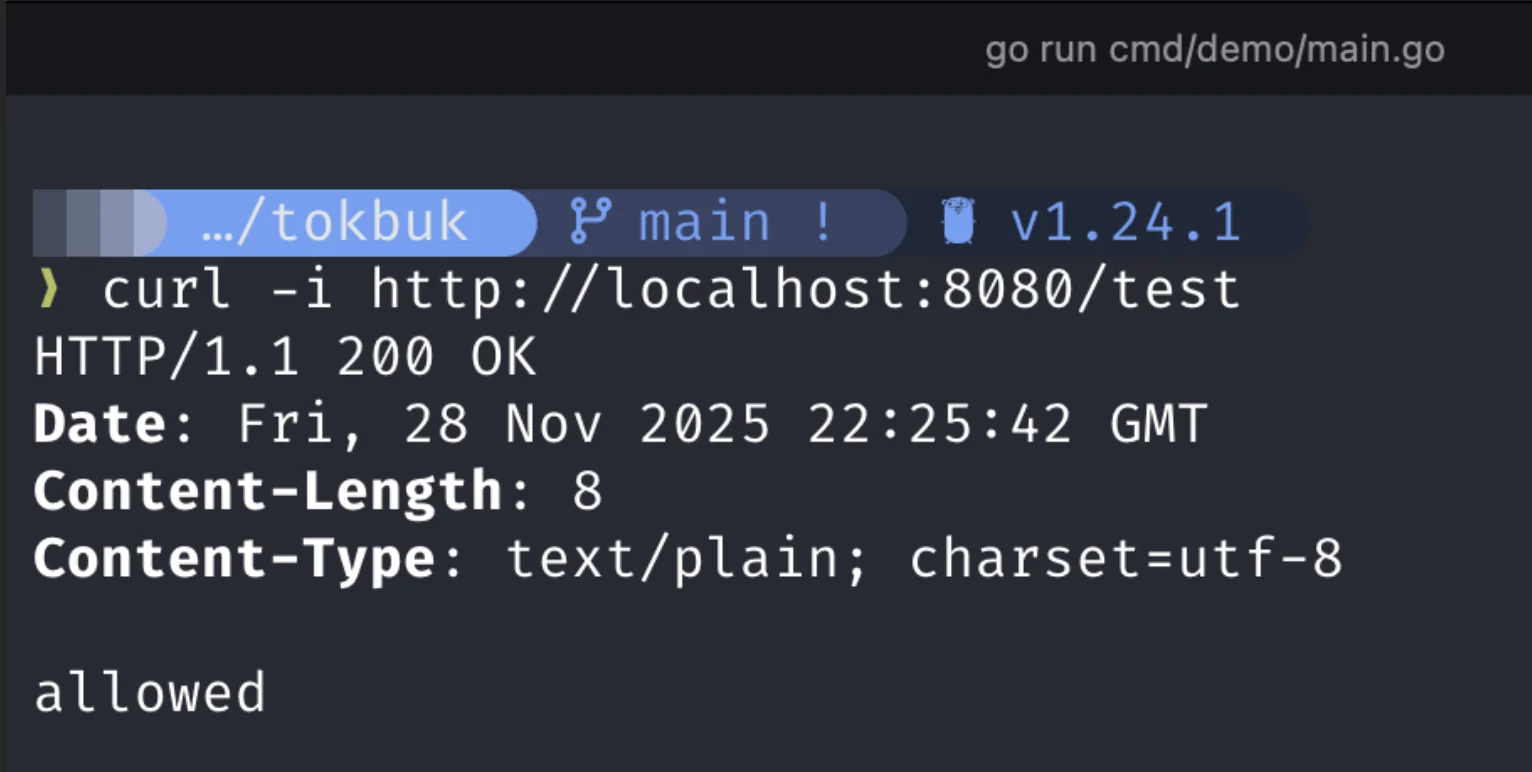

testing the rate limiter

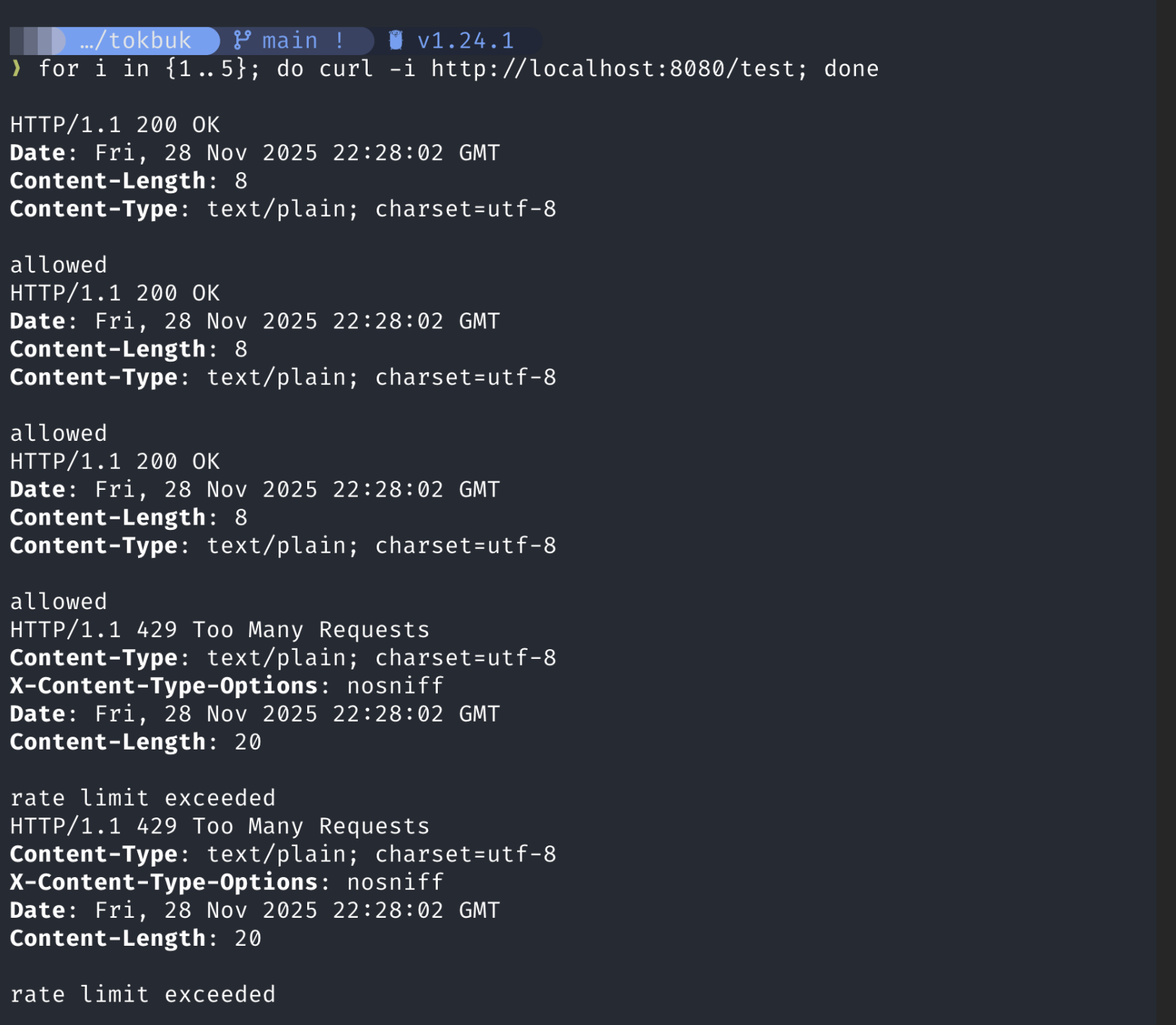

Once the demo server is running, you can test the limiter entirely from your terminal. Using small values like capacity = 3 and rate = 1 token/sec makes the behaviour easier to see manually.

Assuming the server is running at http://localhost:8080/test

send a few allowed requests to test it out:

curl -i http://localhost:8080/test

this is what you should be seeing:

Since our bucket can only hold 3 tokens, sending 5 requests in a tight loop will drain it instantly and force a denial.

for i in {1..5}; do curl -i http://localhost:8080/test; done

Yayyy! Our rate limiter works, the first 3 requests in our burst get accepted since our capacity is 3 and the others are rejected since our refill rate is 1 token/sec.

some limitations with our implementation and why you shouldn't use this thing in prod

- Currently, out BucketManager creates a new bucket for every unique clientID and stores it in a map forever. We never delete them. In production, we would need a background worker to clean up all our unused buckets.

- In a distributed system, we would need to move the token count out of local memory and into something like Redis.

- Our BucketManager uses a single mutex, forcing every single request to wait in the same line to check their limit. At high scale, this becomes a bottleneck.

byee

Writing this blog took me way longer than actually building the rate limiter but I had a lot of fun. I tried to answer all the stupid questions that come into my head about the "why" of doing something instead of just doing it and I hope it made sense.

Anyway, that’s it for me. Hope you got something out of this, or at least understood what I was trying to say. See ya :)