i built my own interpreter and it's kinda cool

So recently i finished building my own implementation of an interpreter from scratch following along the book “Writing an Interpreter in Go” by Thorsten Ball and it’s one of the coolest projects i’ve had the luxury of working on. Here’s a breakdown of what interpreters actually are, and what I learned while building one.

the project repo: github.com/jerkeyray/pika-interpreter

what even is an interpreter in the first place?

The word interpreter was always one of those things I’d hear tossed around with other fancy stuff like compiler or parser. I knew it had something to do with how programming languages “understand” code, but that was about it.

At its core, an interpreter is a program that reads and executes code line by line, without creating an executable binary like a compiler. Take your browser’s console for example, when you write JavaScript in there, each line is evaluated on the spot. That’s why you can experiment and test snippets interactively without compiling a whole program first.

Now as simple as they may sound even interpreters come in a couple of shapes n sizes and the one I built is what’s called a tree-walk interpreter . So instead of compiling to bytecode or jumping straight to machine code my interpreter directly walks the abstract-syntax tree (i’ll talk about it soon) and evaluates each node on the fly.

tokens, lexers, parsers and an abstract-tree

I am gonna spend the next couple of paragraphs talking about these funny words so it made sense to give you a heads up on how they fit into the bigger picture before hand, every line of sloppy code you write goes through a long line of random stuff happening to it before it can actually do anything.

Take this line, for example:

let x = 2 + 2;

The first thing our interpreter does is tokenization, where it breaks down the line into meaningful chunks called tokens. The lexer handles this part. It scans through the text, identifies these tokens, and hands them to the parser, which arranges them into a structured abstract syntax tree (AST) that represents the relationships between the elements.

Next up, the evaluator walks this tree, performing calculations, storing variables in the environment, and executing statements. Finally, the interpreter runs this primed-up AST and produces the output we see.

Now we can finally start digging into how each of these pieces actually work.

tokens and the lexer

The tokens are the “words” of your programming language, my implementation just had these two lines of code defining what a token was

type Token struct { Type TokenType Literal string }

The only thing we need to know about each of our token is its type and its literal value, for example the tokens for the line let x = 2 + 2; are gonna look something like this

// let x = 2 + 2; []Token{ {Type: LET, Literal: "let"}, {Type: IDENT, Literal: "x"}, {Type: ASSIGN, Literal: "="}, {Type: INT, Literal: "2"}, {Type: PLUS, Literal: "+"}, {Type: INT, Literal: "2"}, {Type: SEMICOLON, Literal: ";"}, }

The lexer's job is to take a raw line of code and chop it into tokens like these. It's a simple job but also a critical one. Whenever it sees a keyword like let it emits a {Type: LET, Literal: "let"} token, if it sees a number like 1234 it keeps on reading char by char until the number ends and emits a {Type: INT, Literal: "1234"} token. Same deal for identifiers, operators, punctuations and so on.

parsing and the abstract syntax tree

In the simplest sense a parser is just a piece of code that takes text as input (as tokens in our case) and builds some form of a data structure with it (an AST in our case) - giving our input structure and meaning.

In most interpreters and compilers, the AST is what represents the actual code logic. The “abstract” part means it skips unnecessary details like whitespace, comments, or semicolons. Those are only there to help the parser figure out how the code fits together; they don’t show up in the tree itself.

top-down aka recursive descent parsers

There are two main kinda parsers out there: top-down and bottom-up.

All I know is that top-down parsers construct the root node of the AST first and then branch out downwards while the bottom-up parsers as the name suggests do it the other way around.

Mine is a recursive descent parser. The base idea of the implementation is that for every grammar rule in our language, we write a dedicated parse function for it (this is the reason that the parser.go file in my project is 500+ lines long).

The constructor for our parser sets everything up. It creates a new parser instance, initializes maps for prefix and infix parsing functions, and registers which function handles which kind of token. In short, it tells the parser how to react depending on what token it sees and where that token appears.

func New(l *lexer.Lexer) *Parser { p := &Parser{l: l, errors: []string{}} // initialize parseFns maps on parser and register a parsing function p.prefixParseFns = make(map[token.TokenType]prefixParseFn) p.registerPrefix(token.IDENT, p.parseIdentifier) p.registerPrefix(token.INT, p.parseIntegerLiteral) p.registerPrefix(token.BANG, p.parsePrefixExpression) p.registerPrefix(token.MINUS, p.parsePrefixExpression) p.registerPrefix(token.TRUE, p.parseBoolean) p.registerPrefix(token.FALSE, p.parseBoolean) p.registerPrefix(token.LPAREN, p.parseGroupedExpression) p.registerPrefix(token.IF, p.parseIfExpression) p.registerPrefix(token.FUNCTION, p.parseFunctionLiteral) p.registerPrefix(token.STRING, p.parseStringLiteral) p.registerPrefix(token.LBRACKET, p.parseArrayLiteral) p.registerPrefix(token.LBRACE, p.parseHashLiteral) // infix parse functions p.infixParseFns = make(map[token.TokenType]infixParseFn) p.registerInfix(token.PLUS, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.MINUS, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.SLASH, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.ASTERISK, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.EQ, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.NOT_EQ, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.LT, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.GT, p.parseInfixExpression) p.registerInfix(token.LPAREN, p.parseCallExpression) p.registerInfix(token.LBRACKET, p.parseIndexExpression) // read two tokens to set curToken and peekToken p.nextToken() p.nextToken() return p }

The recursive part of the recursive descent parser comes from the fact that language constructs are often nested inside each other, and the parser handles that by recursively calling itself. It’s easier to see this in action than to describe it.

Take this expression:

(1 + (2 * (3 + 4)))

Here’s what happens: the parser sees the first (, recognizes it as a grouped expression, and starts parsing what’s inside. It reads 1 + (2 * (3 + 4)), parses 1, then the +, and then spots another (. That triggers another recursive call to handle 2 * (3 + 4).

Inside that, it finds yet another group — (3 + 4) — and dives even deeper. This time, it hits the base case: a simple infix expression, 3 + 4. Once that’s parsed, the function returns, and each return “bubbles up” one level at a time, assembling the full AST as it goes.

In short, the parser just keeps calling itself until there’s nothing left to break down.

top-down operator precedence (aka pratt parsing)

It’s easy to parse simple expression such as 5 + 5 or !true. But what happens when things get more complex, like 1 + 2 * 3?

Things get messy when we encounter operator precedence, we need a way to tell our parser to parse multiplication before addition to get the correct result, 1 + (2 * 3), instead of the incorrect (1 + 2) * 3.

This is the problem that Vaughan Pratt solved with his paper “Top Down Operator Precedence”.

The core idea was that instead of baking the logic of precedence into the parser itself, we let the tokens carry that information. Each token type knows its own precedence level and how to parse itself depending on its position - whether it’s a prefix or an infix operator.

We start by categorizing tokens into either prefix or infix tokens based on their position.

Next up we assign something called binding power to each operator. Think of binding power like gravity: operators with stronger gravity pull the numbers around them first. Multiplication has a stronger pull than addition, which is why 1 + 2 * 3 correctly becomes 1 + (2 * 3).

// snippet of the code assigning binding power to each operator type

const ( _ int = iota // 0 (ignored) LOWEST // 1 EQUALS // 2 (==) LESSGREATER // 3 (> or <) SUM // 4 (+ or -) PRODUCT // 5 (* or /) PREFIX // 6 (-X or !X) CALL // 7 (myFunction(X)) )

Let’s take 1 + 2 * 3 again. Since the * operator has a higher binding power than +, the parser handles it first. The numbers 2 and 3 get pulled toward the multiplication, producing 6. Once that’s done, the parser moves on to the addition and calculates 1 + 6.

This system lets the parser handle operator precedence without any giant if-else ladders or special cases. Each operator knows exactly how tightly it binds and when it should stop parsing. Truly peak design with a few simple rules.

evaluating the ast — the interpreter’s brain

Once the parser builds the abstract syntax tree, the evaluator takes over. Its job is simple: walk the tree, node by node, and actually do what each node represents.

At the center of it all is the Eval function. It takes in an AST node and an environment (which keeps track of variables and scopes), then checks what kind of node it is:

func Eval(node ast.Node, env *object.Environment) object.Object { switch node := node.(type) { case *ast.IntegerLiteral: return &object.Integer{Value: node.Value} case *ast.Boolean: return nativeBoolToBooleanObject(node.Value) case *ast.InfixExpression: left := Eval(node.Left, env) right := Eval(node.Right, env) return evalInfixExpression(node.Operator, left, right) case *ast.IfExpression: return evalIfExpression(node, env) case *ast.LetStatement: val := Eval(node.Value, env) env.Set(node.Name.Value, val) case *ast.Identifier: return evalIdentifier(node, env) // ...and so on for every other node type } return nil }

Every node type knows how to evaluate itself.

- Literals like

5ortruewrap themselves into objects. - Infix expressions such as

1 + 2evaluate both sides, then apply the operator. - A

letstatement stores a new binding in the current environment. - A function call creates a fresh enclosed scope, evaluates its arguments, and runs the function body.

The evaluator is recursive by nature. When it evaluates (1 + (2 * 3)), it first resolves the inner expressions and then bubbles the results upward until the final value is produced.

the environment

The environment is a simple hashmap that tracks variable names to values. When you write let x = 10, the evaluator stores x → 10 in the environment. Whenever a variable is referenced later, it looks it up here. For functions, a new enclosed environment is created, giving each function its own scope while keeping access to the outer one.

By the end, the evaluator can handle numbers, booleans, strings, functions, arrays, hashes, and conditionals. It is a minimal runtime that turns plain text into real computation.

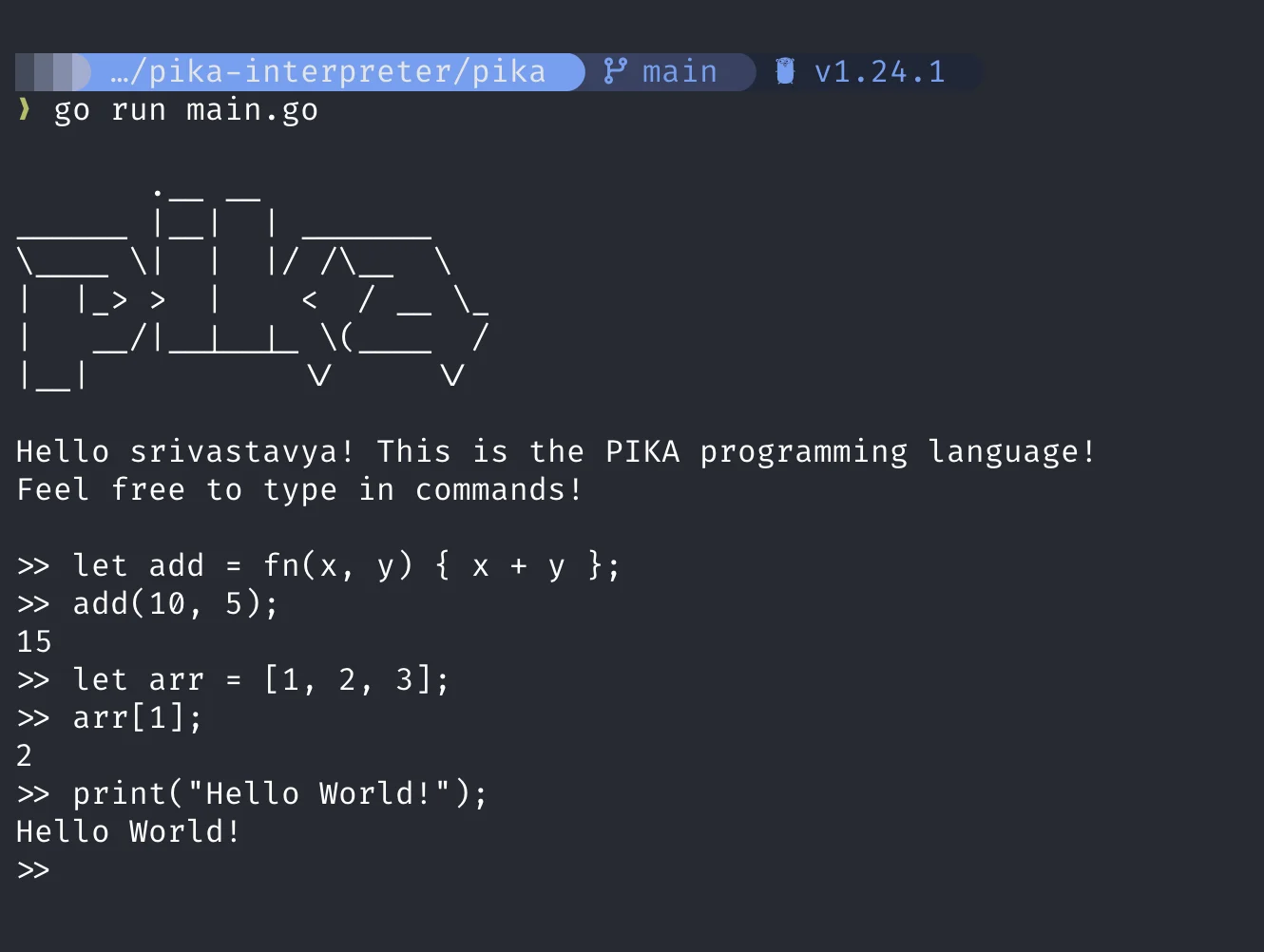

it works now :)

we just taught a machine how to make sense of language btw

Building this project was the most fun i’ve ever had programming by far, even though it was just me reading a book and trying to make it work myself, building out something from absolutely nothing is what makes this job fun for me in the first place. And what’s a cooler thing to build than your own programming language?

Anyway, that’s it for me. Hope you got something out of this, or at least understood what I was trying to say. See ya :)