raft: how distributed systems actually agree

Just like people, making independent nodes agree on anything is surprisingly hard. In a distributed system, many things can go wrong and they do go wrong: networks partition, nodes crash, messages arrive late or out of order and clocks refuse to agree on what time it is. All these problems make the system unable to agree on a single, consistent state. This is where consensus comes in.

In this post, we'll be cover why consensus is necessary, how Raft approaches this problem and all the things that go into making distributed systems agree. This is a no-code language-agnostic walkthrough and focuses more on the why than the how.

why agreement is a problem

Modern software infrastructure doesn't live on a single machine; everything is a distributed system. Databases replicate data across machines. Orchestrators manage containers across clusters. Configuration systems distribute state to thousands of services. In all these cases the system must maintain a single source of truth.

Making these systems agree seems straightforward at first glance. Just have one machine tell others what to do and use timestamps to order the operations. Well if only it were that simple.

things that can go wrong (and eventually will go wrong)

-

Networks are unreliable. Messages get delayed, dropped, or arrive out of order. A node might send a message and never get to know whether it was received, processed or ignored. From the sender's POV, silence is the same as failure.

-

Node failures. A node could be halfway through handling a request and just die. Worse, it might come back with a stale state and have no idea what's going on.

-

Time is not shared. This is a whole other rabbit hole we can dive deep into some other time but agreeing on the current time has always been a tough nut to crack in computer science. Machines can sit next to each other and still disagree what the correct time is, because clocks drift and there is still no absolute notion of time.

-

Partial failure is the norm. Some nodes might be up while others are down. The system rarely breaks, it just fractures.

So no, it's not as simple as picking a leader and ordering events by timestamps. And this is exactly why we need consensus.

the banking problem

Imagine a bank account with a balance of $100.

Two clients send requests at roughly the same time:

- Client A wants to withdraw $70

- Client B wants to withdraw $50

Individually both transactions are valid. Together, they are not.

Imagine if these accounts were replicated across two servers and each server received either of the requests first. Both check the balance and would approve the withdrawal.

Voila, we just created money out of thin air!

This is not an algorithmic failure but a coordination problem.

defining the rules

the consensus problem

Consensus is about guaranteeing a small set of properties that together make a system behave as if it were a single, reliable machine.

The algorithm must satisfy these three conditions:

Agreement - All correct nodes agree on the same value.

Validity - If a value is decided, then it must have been proposed by some node. (i.e the system cannot just make up values).

Termination - Every non-faulty node must eventually reach a decision.

These three properties are the minimum requirements a consensus algorithm must satisfy.

agreement resists divergence. validity resists fabrication. termination resists deadlock.

This is where Raft comes in.

CAP theorem

The fundamental constraint of distributed systems that states a distributed data store can only provide two of the following three guarantees at the same time.

Consistency - All nodes see the same data at the same time.

Availability - Every request receives a response, even if it's not the latest.

Partition Tolerance - The system continues to operate despite network splits.

In real-world systems, partitions are not optional. Networks fail. Machines lose connectivity. So Partition Tolerance isn’t a design choice, it’s a requirement. Once you accept that, you’re left with a tradeoff between Consistency and Availability.

Raft chooses consistency over availability when network partitions occur because inconsistent data is catastrophic but unavailability is just a nuisance.

When the system cannot guarantee a consistent view of state, it refuses to proceed. It will stop accepting writes rather than risk diverging histories.

So, going back to the banking problem. If the system cannot be certain about the order of operations, it would rather reject both withdrawals than allow an incorrect balance to exist.

We maintain correctness instead of maximising uptime.

before raft

The standard for consensus was an algorithm called Paxos. While it's mathematically proven correct, Paxos is notoriously difficult to understand and even harder to implement.

If an algorithm is too complex for engineers to reason about, they will implement it with bugs. Raft achieves the same performance and safety as Paxos while not making engineers bash their heads.

raft: the mental model

Now that we have clearly defined what problem consensus solves and what it is, we can finally talk about the mechanism behind it.

Raft is built around the concept of a Replicated State Machine (RSM).

The idea is simple: if you have two deterministic state machines and you feed them the exact same sequence of inputs, they will end up in the exact same state.

This sequence of operations is called The Log.

It is Raft's job to ensure each node has the same log.

terms

We've already discussed how real clocks are unreliable in distributed systems. Hence we need a different mechanism to order events across different machines. Raft fixes this by introducing the concept of a term.

Time in Raft is not measured in seconds, but in terms.

A term is a monotonically increasing number that acts as a clock for the cluster.

Each term begins with a leadership election. Every message carries a term number. Nodes always defer to messages with the higher term.

This is Raft's solution to the problem of time.

leader election

Instead of all nodes talking to each other at once (which gets messy), Raft elects a Leader.

Each node starts as a follower. If it doesn't hear the leader's heartbeat in a while, it assumes the leader is dead and starts an election.

This node becomes a candidate:

- It increments its own term.

- Votes for itself.

- Requests votes from other nodes.

The other node will grant its vote if:

- The candidate's term is at least as up-to-date as its own.

- It hasn't already voted in that term for someone else.

If a candidate receives the majority of the votes (quorum), it becomes the leader and starts sending heartbeats to the other nodes to assert dominance.

Randomised timeouts reduce the chances of multiple nodes starting their elections simultaneously, which prevents deadlocks.

log replication

Once a node becomes a leader, it becomes the single point of entry for all client commands.

When a client sends a request:

- The leader appends this operation to its local log.

- It sends the new entry to its followers via

AppendEntriesmessages. - Followers append the entry if it matches their log.

- Once a majority have acknowledged the entry, it is committed.

If two nodes contain an entry with the same index and term, then their logs are identical.

This makes sure that if an entry is committed:

- no future leader can change it.

- it will never be lost.

- it will eventually be applied on all nodes.

lifecycle of a request in raft (mental flow)

- A client sends a command to the leader. (e.g. SET X = 5)

- The leader writes this command in its local log but does not execute it yet.

- The leader sends

AppendEntriesmessages to all followers. - Followers receive this message and check whether their previous log entry matches the leader's.

- If yes, they write the entry to their own disk and return OK.

- If no, they reject it.

- If the leader receives "OK" from majority of the nodes, the entry is committed and the command is executed.

- In the next heartbeat, the leader tells its followers "the entry is committed" and the followers execute this command on their own machines.

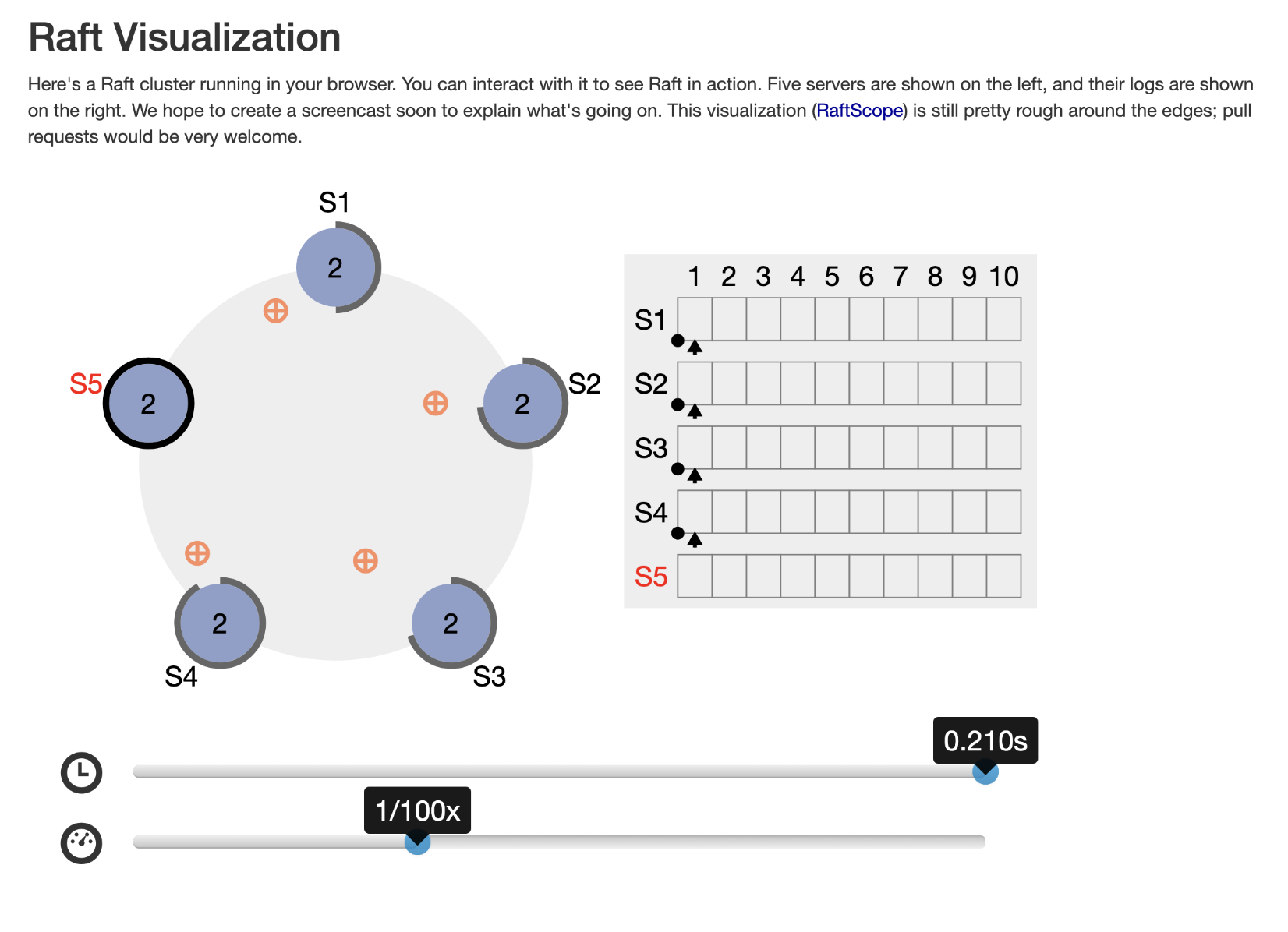

go check out this neat little Raft visualiser.

engineering raft and some technical stuff

persistence

Raft assumes that the machine state survives process restarts. Without this a node could forget past decisions and violate our safety guarantees.

At the very minimum, each node must persist:

currentTerm: to ensure it never goes back in time.

votedFor: so it doesn't vote twice in the same term.

the log: because obviously.

These must be written to a stable storage before a node acknowledges anything to the rest of the cluster i.e. a node shouldn't be responding before persisting else we risk the system having an inconsistent state.

RPCs (in short cause that deserves its own blog)

To understand how Raft coordinates its nodes, we need to think about how nodes talk to each other in the first place.

In a distributed system, one machine cannot directly call a function to another. There is no shared memory, no shared stack, no shared execution context.

The only way nodes can communicate with each other is by sending messages over the network.

A Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is an abstraction that makes this message look like a normal function call.

Under the hood, an RPC:

- serialises a request into bytes.

- sends it over the network.

- waits for a response.

- deserialises the result.

Raft could use any specific transport mechanism. Be it HTTP, TCP or pigeons. RPCs just provide the clean abstraction that makes our lives easier.

AppendEntries RPC

Almost everything in Raft happens through this single workhorse RPC.

It has two critical jobs:

- sending new entries to followers (as the name implies obviously).

- sending heartbeats to assert that the leader is alive.

Each AppendEntries RPC contains:

- the new log entry

- the index and term of previous log entry

- the leader's current term

Followers only accept an entry if their own log matches the leader's up until that point. If it doesn't, they reject the request and the leader backs up and tries with an earlier log index. This back-n-forth continues till the logs align.

handling retries

Clients always send their requests to the leader. If a client contacts a follower instead, the request will be redirected to leader or outright rejected.

This ensures all state changes happen through a single authority.

Suppose a client sends the leader a request, and the leader crashes before responding. The client has no way of knowing whether the operation succeeded or not. When it retries, the request might be processed by a new leader.

To handle this, the system relies on idempotency:

- clients attach a unique id to each request.

- server tracks which request has been applied.

- duplicate requests get ignored.

This ensures that retries never result in duplicated state changes.

avoiding race conditions

We don't need to.

Yep, if you think about it Raft's safety doesn't depend on time. Messages can arrive late, out of order, or not at all. Nodes can act on stale information. None of that breaks correctness.

Raft's design works on strict rules - terms, log indices and quorums to decide which operations are valid.

So in Raft, by design we don't even need to prevent race conditions because they are rendered harmless.

log compaction

In a long-running system, the log grows without bounds. Keeping a track of every operation ever is neither practical nor necessary. Once the effects of older log entries have been applied to the state machine, those entries aren't necessarily needed to keep track of the state.

Raft fixes this with log compaction through snapshots.

A snapshot captures the current state of system at a point in time. Once this snapshot is created, earlier entries can be discarded since their effects are already reflected in the state machine.

This keeps storage usage and recovery times in check, without compromising on correctness.

cluster membership changes

Nodes are constantly being added and removed over time in our cluster. Membership changes in our cluster are dangerous because it alters who forms majority. If done incorrectly we could have two different majorities at the same time and our system would break.

Raft solves this through an intermediary state.

Instead of changing from the old state to new state in a single step, Raft goes through an intermediate state where both the configurations are alive at the same time. During this state, any decision must be accepted by a majority of the old and new configurations.

Once the new configuration is established, the old one is safely discarded.

byee

I recently built my own Raft-based distributed KV store called Mimori. This post is my attempt to answer all the questions i had while trying to make sense of Raft.

The point of this boring post was to make Raft feel boring to you, because that's exactly what it is. I won't sit and pretend like this is some mystical and impressive tech when it's not. Distributed systems are grounded and mechanical by design and that's exactly why they work.

Anyway, that’s it for me. Hope you got something out of this.

Thanks for reading. See ya :)

If you found this write-up useful, feel free to fund my caffeine addiction: